Sundays in Arequipa are currently focused on prayer. Personally, I have felt convicted to pray more about the work. Knowing the prayerfulness of some brothers and sisters who are worthy of imitation, I always feel I should be more prayerful. The difference now is that I am feeling called, urged, prompted to pray. I hesitate to say "more," though, as if the issue were quantity. It is, I think, about a way of seeing the world—perceiving the need to live, think, and speak more according to the way things really are. Prayer, it seems, is often a matter of listening and looking, hearing and seeing, fixing eyes and mind on a dimension of reality that we call unseen.

Church in Arequipa: CeDeTe

Church in Arequipa: Commitment

Part 10: Theological Education as Missional Equipping

No one is really in a position to say what missional means—it’s still under negotiation among those who care about the precision with which we use words connected to important ideas. The ideas to which missional is connected are very important, in my opinion, but the discussion of the word for the last decade or so has been especially fraught because it is also about a movement. Local expressions of Christianity are changing, and some (hopefully much) of what is emerging is about a realignment with God’s mission. In part, this means recontextualizing the gospel, and therefore the church, in Western postmodern subcultures. And in part it means correcting some of the assumptions and structures that have long prevented congregations everywhere from participating in God’s mission to the extent they might have.

Part 9: Decision-Making and the Offering

After months of studying the offering, at our last general meeting the Peruvian disciples made some decisions about our collective practice of giving as a network of house churches. Each group will have an envelope available at every Sunday meeting, placed somewhere out of the way, in which those who wish can discretely place their offering. Two people will count the offering together after the meeting, seal the envelope, record the amount, and both sign the envelop. The church elected Etelvina, Paty, and Alfredo to administrate the money received.

Part 8: Membership

How do you suppose the early church thought about “membership”? Or did they? Of course, the New Testament doesn’t mention anything about it. There are a number of references to specific house churches, which were identified by the owners of the houses (Rom 16:5; 1 Cor 16:19; Col 4:15; Philem 2). This doesn’t tell us much except that the owners were fixed members of particular congregations.

The Better Question

In 2005, Kyle and I flew to Lima, Peru for the Pan American Lectureships. We hoped to gain some perspective on the Peruvian church and meet other missionaries from around Latin America. We were aware that the “marriage-divorce-remarriage” controversy had split the Peruvian church. In fact, in addition to the usual Lectureship activities, some of the visiting missionaries attempted to bring the two sides together for the first time in many years. It was and is an ugly situation.

As observers still years from entering the mission field, we did not expect the controversy to touch us personally. Moreover, while the conflict was clearly real, it all seemed caricatured—tales of preachers trained to travel around and insinuate themselves into congregations in order ferret out the false brothers; which is to say, in order to split churches. Fixating on an issue or reducing salvation to a single conclusion is one thing–a historically typical thing—but a country-wide witch hunt was another thing altogether. It was surreal.

Then a young Peruvian preacher who had heard were were planning to work in Arequipa approached us during a coffee break. “I hear you are going to Arequipa,” he said. “Yes, that’s right,” we responded. “What do you think about marriage-divorce-remarriage,” he inquired directly. There was no avoiding the confrontation. It was already pursuing us.

Yet, we’ve had no part in that internecine strife. Instead, our friends’ marriage struggles have confronted us. What Scripture says about marriage has come alive as God’s own wisdom for living well in our most challenging relationships. It is only by contrast that the tragedy of using Scripture as a bludgeon to defend one’s legal verdict. The urgent question that comes from every direction is not whether one is allowed to get divorced or remarried but how to stay married despite the difficulty it involves. The former is a question worth exploring, but the latter is far more important. Jesus himself said that divorce existed because of hardness of heart—the same affliction that he diagnosed in his apostles—which leads me to believe that the more fundamental question in his mind was how to soften hearts. Our friends who ask for biblical guidance to better their marriages are not asking which commandments they must obey but how to obey. They are asking to be discipled; they are asking for softened hearts. Imagine if the Pharisees had asked that instead. Imagine if the Peruvian church had.

Requests for sound counsel led Abraham and me to offer a marriage seminar, which we recently completed. For five Saturday evenings we explored the nature and purpose of marriage. The sixth and final class was cancelled because of José Luis and Miriam’s wedding. Preparations for the ceremony were more than they could manage alone, but the church members worked together to make it happen. It was a tremendous thing to witness the church rally behind Miriam, who is a new Christian, and bless their union with service and love. I much prefer to see the unity of the church upholding a marriage than to see a teaching against divorce dividing the church.

Time Is on My Mind

Sherwood Lingenfelter and Marvin Mayers published a little book called Ministering Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Personal Relationships in 1986 that is now in its second edition. It is a worthy introduction to both the concrete application of an incarnational missionary approach and the use of anthropological paradigms in mission work. I’ve adapted some of it this year for the internship. The book features a simple questionnaire, the responses to which allow one to plot several of the respondent’s basic cultural orientations. This exercise, in the first place, allows the missionary to know his- or herself better. But I’ve also set the inters to the task of translating the questionnaire (in language class) and surveying random Peruvians. This gives us the opportunity to compare our orientations as Americans with our Peruvian neighbors’.

There are all kinds of reasons that this exercise is of limited value empirically. We have not ensured that the translations communicate as well in Spanish as they do in English. We have not attempted to understand the cultural biases that might be affecting the survey methodology itself. And we certainly have not surveyed a statistically significant sample size. But the results have stimulated profitable discussion nonetheless. I will share an observation gleaned from one of our conversations.

Each cultural value surveyed is coupled with a corollary value and plotted on an X–Y axis. In other words, for each value there is another value in tension with it, but Lingenfelter and Mayers do not construe this tension as polar. For example, there is time orientation and event orientation. The graph on which they are plotted looks like this:

Thus, one can be high or low on either orientation, in many different combinations. The book provides the following summary explanation of these two values:

So how do Americans usually test? You might easily guess: higher on time than on event. Between myself and the interns, the average scores were about 4 on event and 5 on time. These scores, I suspect, reflect the interns’ stage of life (incidentally, this is and example of why statistical validity matters). The authors hypothesize that the average American is at about 2 on event and 6 on time. The point is, Americans generally value time (“time is money”) markedly more than event.

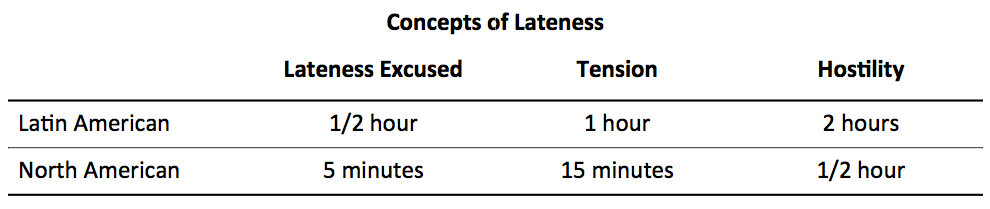

We also have expectations for Peruvian results. We expect Latin Americans typically to be less time conscious than North Americans. For example, Lingenfelter and Mayers characterize the difference in terms of tolerance for lateness:

While we have definitely struggled with this difference, my study of Peruvian culture has often been a process of overcoming generalizations about Latin America when they do not apply to Peru. One point of confusion for an American trying to interpret the behavior of Peruvians is actually not their concept of lateness but their inconsistency regarding time orientation. (Note: I am not referring here to variance in individual personality, for which Lingenfelter and Mayers allow in a given culture.) I think it would be easier (for me) to adapt and experience church life accordingly if the apparent Peruvian time orientation were uniform.

There are major facets of Peruvian life that are clearly time conscious, such as work and school. Even here there are notable differences from American modes of operation, but generally speaking, employees in the business sector are expected to be at work on time and are penalized if they are not. Formal businesses open and close when they are supposed to and movies show on time. Children are expected to be at school on time (I’ve been reprimanded for dropping off the kids late because of traffic).

Yet, there are other aspects of life that are radically event oriented. I was just invited to a party scheduled for 7:00 pm, with the caveat that people won’t show up until 8:00 or 8:30. Compare that with the Latin American concept of lateness above. For parties, excused lateness is an hour to an hour and a half. Family gatherings, which are frequent, function similarly.

So how did Peruvians score on our questionnaire? Admittedly not how I expected—but just how I might have expected had I thought more about the above dynamics.

I have to reiterate that we can’t possibly take these survey results as statistically valid—there may be some factors skewing the respondents’ answers (such as their understanding of the Likert scale), and we are not working with a representative sample. But after considering the results, there is something at least intuitively right about them. Peruvians feel compelled to affirm strongly both time and event. There appears to be a pressure within the culture to hold these two values in significant tension.

I speculate that, were we to conduct the same exercise in rural Peru, we would find event to outweigh time greatly. The stereotypical portrayal of Latin American countries like Peru, I believe, reflects traditional cultures. In a city like Arequipa, where globalized modern paradigms such as those of business and education demand conformity far more than they adapt to local culture, there is a powerful compulsion to value time in the same way those paradigms’ countries of origin do. This comes as part of a very aggressive narrative about the meaning of progress, development, accomplishment, capacity, and power as a country. The narrative’s implicit claim from grade school on is that success in the global marketplace is contingent upon valuing time, for example, in the same way one’s competitors do. This is a prerequisite to success in education (Peru adopted the American education model) and in business. I believe this is a possible explanation for why Peruvians, who traditionally value event, would respond to our survey in a way that equally values time.

Though we might critique this phenomenon extensively, that is not the aim of the present article. Whether good, bad, or both, the contextual reality is what concerns me—how do we locate our experience as church within this value system? As missionaries, what tendencies do we affirm or reject, what values do we incarnate, and how do we interpret our Peruvian neighbors’ interaction with us and each other?

Because our value system is truly time oriented, our tendency has been to ask, “If they can be punctual to work and school, why not to church meetings?” We interpret Peruvians’ behavior quite literally in terms of value: they must think church is less important than work or school, if they cannot accord it the same effort. After all, it is evident they can come on time if the want to. You can see how our values function to shape our reasoning. But this is not the only reasonable interpretation.

In fact, some of our explicit intentions as a team should lead us to a very different conclusion. We are working to establish a non-institutional ecclesiology. If it is institutions such as work and school that demand punctuality, Peruvians showing up late to our meetings should be a kind of affirmation that we are succeeding. Moreover, their treatment of church in terms of event orientation suggests that they view it more as a family gathering, which should be positive for us, since our fundamental paradigm for church is family. Similarly, we might compare this event orientation with their disposition toward parties. Scholar Justo González has postulated that culturally attuned Hispanic worship is essentially experienced as fiesta (party) (Justo L. González in Justo L. González, ed., ¡Alabadle!: Hispanic Christian Worship [Nashville: Abingdon, 1996], 9-28). If Peruvian Christians are experiencing assembly as family, fiesta, or both, we should be thankful to God; and we should also expect them to show up late!

These conclusions might have been obvious to others, but it was in fact the process of talking through the survey results that, after four years in the field and a significant amount of previous study, finally helped me to see the reality of our cross-cultural struggle differently. My deeply instilled values still dominate. I am not one of those missionaries who finds acculturation easy. Appreciating the differences cognitively is one thing; really seeing the world differently is another. But I do feel less frustration when I manage to grasp little insights such as these. I’m grateful to the interns for participating in the survey process.

New Life

Jose Luis was the first Peruvian that was baptized into Christ in our time here. I can remember our first meetings with only the two missionary families, Emilio (who was already a Christian), and Jose Luis. How exciting it is to see what has happened over the course of these almost-four years. We have grown in number, but more than that, we have grown in our relationships with so many of these Peruvians. I commented to one of our interns that it is kind of scary for me to think about leaving Peru at this point. I am so invested in the lives of these people, my Peruvian family, that I cannot and don't want to imagine the day when we leave.

Throughout the first part of this year, Jose Luis's attendance to our weekly meetings were off and on. He works a lot, and we were aware that his work sometimes affected his attendance. What we were not expecting to hear one Sunday is that Jose Luis was gone a lot of weekends because he was visiting a certain friend in another city...

Meet Miriam. She is promised to Jose Luis and they will wed this August (the 18th to be exact). She lives in a town 4 hours away from Arequipa. She will move here the beginning of August. She has been studying the gospel message with Jose Luis throughout their courtship. They requested to come meet with Greg and me a few Sundays ago. We felt so honored that she would make a special trip to come meet us. But that trip meant more than that. Jose Luis explained that she wanted to join him in his journey with the Lord. We scheduled a time to meet again and talk about the cost of discipleship. They came, we talked, and Miriam decided to go with the “Eunuch response.” If there was a place to do the baptism, she didn't see any reason to wait. On June 29, the holiday of Peter and Paul here in Peru, Miriam confessed her faith in front of the church that could come with 2 hours notice. It was a beautiful scene. We all came back to the house. We shared, sang, and prayed. Keep Miriam in your prayers as she begins her journey of discipleship. Also pray for the new life Jose Luis and Miriam will share as they say their wedding vows this August.

Toward the end of this month, I finished the study of Mark with Nadia. I went into that last study feeling so excited about Nadia making the commitment. The result caught me off guard. To make a long story short, I learned that Nadia had a different perception of baptism than what I believe the Bible teaches. She explained to me that she is in the process of making that commitment but she needed to forgive some people in her life and make things in her heart right before she could make covenant with God. I immediately went to Romans 8 where it talks about the Spirit helping us in our weakness. We conversed for awhile, and we concluded with the plan to look more closely at baptism in our next study. I spoke with David Mitchell, the overseeing elder at Cedar Lane of the Peru work who was here with the engineers, and with Greg about where I should go with this conversation. I fully believe the Spirit pointed me to Romans 8, so it was no surprise to me when they both said I should take her through Romans 6-8.

Also, I spoke with three of our Peruvian Christians that came from a Catholic background– Paty, Alfredo, and Manuela. I learned from them that Nadia's hesitancy comes from a Catholic mindset of not being able to approach the presence of God unless your horizontal relationships are made right. I learned a lot from them, and I thank God that I have my Peruvian family that understands a Peruvian mindset better than I ever can. Isn't that what Christian brothers and sisters are for?

Nadia and I read through Romans 6-8, and we ended the meeting with her saying that she was ready. She realizes that she is in process, but that she will always be in process. Baptism isn't the end result of making yourself who you think you should be. Baptism is the beginning. It is the acceptance of the gift of the Holy Spirit who is the only answer for making us into the person God wants us to be.

We haven't made it to the water yet, because there are some people that Nadia really wants to be there to witness her decision. We are making plans for that special day. I am thrilled beyond words to have walked thus far with her in this journey. God has taught me and stretched me so much in the process. I am now excited to see her confess her faith publicly in front of the saints, and enter into a study of discipleship with her. Thanks to all of you for your prayers for Nadia. She is such a dear friend to me, and I cannot express the joy I feel in being able to call her “sister.”

2012 Interns

When I was at Harding as an undergraduate—and as I turn 30 I'm coming to the realization that it's been longer than I was imagining—I remember wishing that there was an internship for Latin America comparable to the one for Africa. Africa was the primiere destination for the missional student, and it seemed that the program was pretty great. I began to dream then of creating a comparable internship, once we got to the field, that could provide students interested in Latin American missions another opportunity. I'm guessing that the Africa internship at Harding is still the main event, and for good reason. But it's been fun to see our efforts here evolve into a multi-university, seven-intern experience.

I thought you might like to meet the students who have given their summer to learn and serve in Arequipa.